What is Government?

A short story about a founder trying to sell to the government.

This fall, we were lucky to have Atharv Gupta join us as a fellow. Over the past few weeks, he’s explored our ecosystem, met many of our closest collaborators, and learned the unwritten rules of government contracts, from those who have lived by them. Those conversations sparked a short story that captures the spirit, humor, and excitement of working with the government today. You can read more about Atharv in our introduction post on the blog, and the complete “What is Government” story below!

Founders everywhere want to build for the government again. The hard part is getting the government to buy.

I saw this firsthand over my fall fellowship at Also Capital, so I wrote a short story about it.

WHAT IS GOVERNMENT is the story of a founder, Phil Stack, trying to sell his tech to the military. It’s based on 20+ interviews with folks including Delian Asparouhov, Eric Lasker, Nate Loewentheil, Connor Love, Daniela Perlein, and several other founders, VCs, GTM operators, and ex-military & govt officials.

In this story, Phil meets his investor (Angelica Rounds), his head of Government GTM (Max Clarence), and a procurement officer (Connie Tract). Through them, we learn all about the government that Phil encounters.

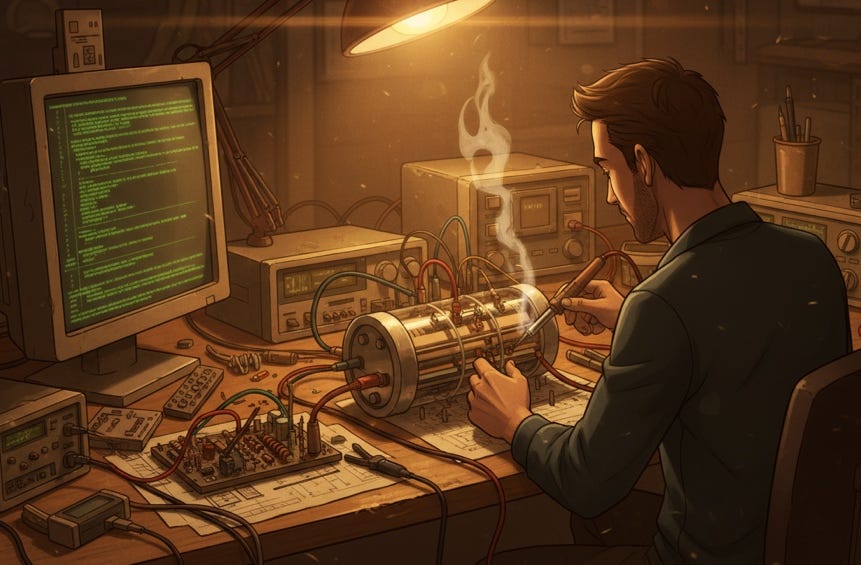

Meet Phil Stack, a founder.

Phil has just launched a start-up. The goal is to build edge deployable power systems through cutting-edge batteries.

But all that is secondary to the mission: building a great, American company.

Phil has quite the resume: several years at SpaceX, a stint at a start-up, and a master’s in materials science to boot. In his DNA are dual traditions of risk and service from engineer grandparents expelled from their own country, forced to start anew in the United States. Not as engineers – dreams left behind in dictatorial rubble – but as entrepreneurs, first with a corner store of their own, turned franchise, turned foothold.

But more than that, he’s borne witness to a changing world. It’s a world where government’s inability to deliver on promises – healthcare, education, infrastructure – have rent fault lines in his country asunder. It’s a world in which the US government is playing an active role in technology markets, for it is desperate for these tools.

Money and attention pour forth, creating a petri-dish upon which founders are multiplying. They are targeting customers ranging from the US Army to local school districts.

He feels proud to be one of them.

Phil finds that the oft-mythologized path to founder-hood holds true in most forms. As his hours are subsumed by bleary nights of code and pitch decks, expos and MVPs, happy hours and warm intros and cold calls, he remains awed at the whole endeavor.

He builds. His team builds.

And much of it hinges on the government buying his product.

He’s heard a lot about this government of his. He hasn’t been to DC since an 8th grade field trip but has voted a few times. He feels at-once like an ardent supporter of the American project and at-once deeply skeptical. He’s been around tech long enough to witness a shifting culture around patriotism. Over hor d’oeuvres and beers, people have told him that the government is everything right with this country, everything wrong with it, and everything in between.

That it is at once friend and foe, obstacle and oxygen, and ultimately, customer.

So, Phil. What exactly is this government you’re trying to sell to?

Part 1: Government is Desperate

Angelica Rounds was connected to Phil Stack via an email forwarded by a friend of a colleague, the typical inevitability of happenstance that defines these early deals.

Her path into VC was as improbable as anyone else’s, a circuitous journey through the Air Force and a Wharton MBA. With a dollar, a hunch, and a newfound network of founder friends, she made her first angel investments. A few years later, with that hunch validated, she’s now raised her first fund, with the goal of backing founders bringing sorely needed innovations to all facets of government.

Her hunch is nothing new. Folks in all levels of government have been talking about the innovation gap for decades. She’s seen firsthand how the defense primes have run aground yet still maintain their stranglehold. Even as Washington turns over every year, Lockheed and IBM and Boeing, and their offices and factories across fifty states, don’t. The same holds true across all sorts of verticals, for city councils, school districts, police departments, clinics, pharmacies, and more.

But VC has finally caught up. A few moonshot bets in the 2010s, a narrative shift in the 2020s, enough to create a ripple turned wave, large enough that every VC in town had to launch their own government, defense, and hard tech theses to stay relevant. Subsequent start-up successes, from gold-standard mid-market acquisitions to Series rounds stretching deeper into the alphabet (all the way to the letters ‘I-P-O’) turned this wave into a veritable flood of capital. LPs, perhaps a few years late, are now clamoring for exposure to ‘Defense’ and ‘Government’ asset classes, unthinkable only a few years prior.

Angelica has managed to siphon a thimbleful of all this into her first fund.

The big VCs have armies of lobbyists and operators in DC devoted to their theses, sprawled across the administration and the Pentagon. Others even embed their own tailored government-sales teams onto portfolio companies directly. These VCs, her far-off competition, are no longer just betting on the future to come, they’re actively realizing the future they desire. When founders ask these VCs, ‘On day one, what can you do for me?’ it’s often easier for them to answer: “Let’s start with what we can’t do.”

Angelica doesn’t need all this. The big players need the headlines and soaring exits to justify the spend. But she just needs to execute a fraction better than others. It’s a patient strategy – there can be no other kind with government customers – and Phil’s deck scratches the itch she was waiting for.

In advance of their call, Angelica keys through Phil’s minimalist slides but finds her mind wandering. She’s sitting outside on her patio. The autumnal sun sings against the backdrop of crisp air, and its glare illuminates every fingerprint on her too-dark laptop screen. The specs of Phil’s batteries don’t go over her head – she’s done enough research in that sense – but she knows that the success of this investment will hinge elsewhere. She wonders what she will tell him that the other VCs won’t.

The big investors proclaim that it’s never been easier to sell to the public sector, that government is the best customer it’s been since World War 2. Those adherents need not look far to find evidence, from Executive Orders to billions earmarked in OBBBA and the NDAA for innovation, to Army Secretary Driscoll who put it more eloquently: “We cannot fucking wait to innovate until Americans are dying on the battlefield.”

But the VCs, of course, have to say this. It’s the only assumption that can close the chasm between the expectations of venture-level returns and the bitter realities of procurement. As start-ups multiply with promises of rockets and robots, she only senses that chasm growing wider. Plenty of observers instead say procurement reform is Washington’s white whale. Money alone, along with any number of alphabet skip-the-line mechanisms – OTAs, OSC, SOCOM, FUSE – cannot change fundamentally mismatched cultures.

Not for the first time, Angelica wonders where on the spectrum she falls. She pinches the bridge of her nose and tips her head back, letting the sunlight warm her closed eyelids.

Deep down, she thinks it’s a false spectrum. All the handwringing and hype obscure a simple fact.

If the government likes what you’re making, then you have a shot.

If any of its legions of program officers, legislators, generals, and CIOs have spotted your diamond in the rough and believe in it, then you have a chance to make it. Mentors and peers of Angelica’s who had sold to the government before, whether through In-Q-Tel, retired officials on their board, or just grit, have told her that once you make it, the government is the easiest customer a company will ever have.

She agrees with one thing – the government has never been more willing to spend its money on tools like Phil’s. Whether it happens or not is dependent on a world beyond her. But soaring deficiencies in every facet of public services may have finally met changing mindsets.

Perhaps when Angelica logs into her Zoom meeting with Phil in four minutes, what she’ll say is this: Selling to the government will never be easy, but the government is desperate for his product.

Perhaps that’s enough for a thesis.

Part 2: Government is Champions

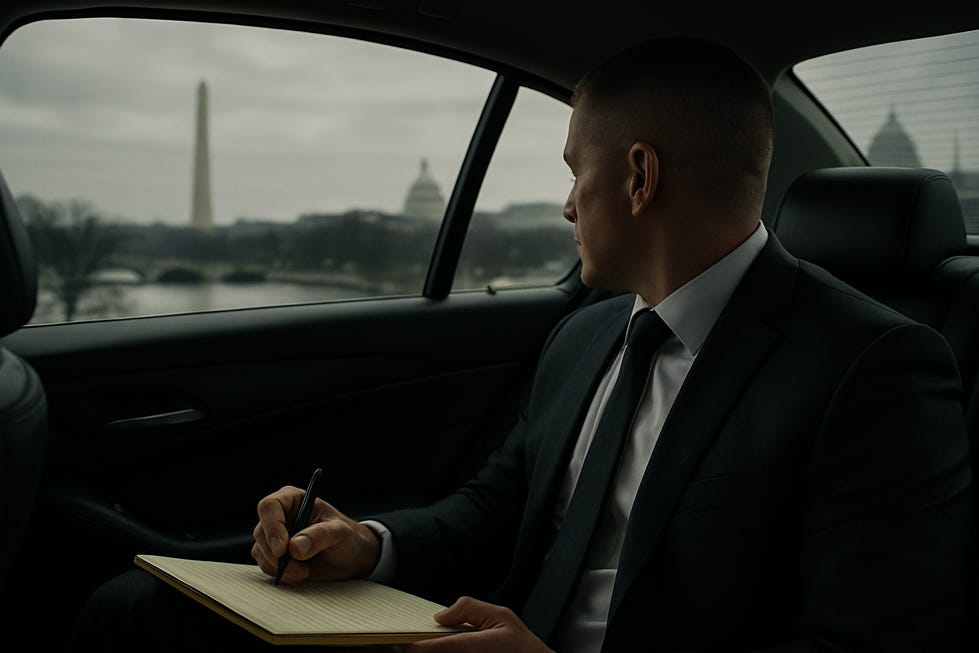

January in DC is a grey month. A watery sun fights to be heard through wooly clouds, leaving the white marble facades of the nation’s capital, its stoic columns and monuments, bathed in tired light. The dryness in the air violently contrasts with the now-forgotten summer’s swamp. Metro cars are filled with cracked lips and fraying coats.

“One more time,” Max Clarence says to Phil, sitting in a nondescript Tatte a short Uber away from their meeting.

“We’re looking for our champions.”

The two sit face to face over a disintegrating pastry. Phil looks out of place in his suit and tie. Max knows it’s one thing when procurement folks, generals, or legislators visit the factory floors. There, they want to see the flip flops, the wild hair, the errant dry erase marker streaks. DC is a little different – he had to encourage Phil to get a haircut and wear a tie – but those alone make not a government vendor.

Max overlapped with Angelica years ago at Wharton. After she wrote Phil his first check, he was her first call. She said she had just met a bright founder with a product that would sell itself, if only he could help. A few site visits later, and Max quit his job to join the team.

Max has been selling things to the government for a long time. He knows better than to consider himself an expert. One of the perks of living in a democracy is that every piece of information you could want about selling to the government is a few ctrl-f’s away in some PDF. But years at his old company, nonetheless, honed him into something close. There, he was onboarded with a whirlwind presentation and laminated binder on the Pentagon’s alphabet soup of terminology. Soon thereafter, Max found himself sitting before Generals at the ripe age of twenty-eight.

“Just so I’m clear,” Phil says in between sips of a lukewarm flat white. “There’s two parts to all this. The first is finding someone who wants what we’re building. Check. And the second is just finding someone who’ll let them pay for it?”

Max thought the word just was doing a lot of heavy lifting there, but Phil was essentially right. His batteries performed well at early expos, enough that they had gotten an on-base pilot. That side-by-side feedback, by the hour for a whole week, transformed a flimsy proof-of-concept into something viable.

“I’ve seen a lot of these processes blow up.” Max says. “I’ve seen Admirals and CIOs gush over a pilot program and still wait years before they get their hands on it. It’s the same question every time: Did you find someone willing to stick their neck out for you?”

“Thanks for the vote of confidence,” Phil says dryly. He takes another sip. “So. What exactly makes a champion?”

Phil has landed on the question that people spend their entire careers trying to answer.

The optimist in Max believes it’s mission-alignment, from a school district to the military. Will operators use your tool? Did you sit shoulder to shoulder with them and offer respect for their expertise? Will you match the culture you’re entering? If so, they’ll bend over backwards for you.

His cynical side says something else. Relationships and expectations are everything. People won’t do shit for you if they don’t know you. A friend of a mayor, even a bought friend, trumps a superior engineering team every time. Every program officer is evaluated on whether they spend their budgets. It’s a black mark if they don’t, and they all have a smorgasbord of easier things to spend on.

And the romantic in him still says it’s conviction. A true believer. Someone with the conviction to do a hard thing because their country and community need it. He knows there are change agents in every agency. He’d spent months trying to convince skeptics before, industry veterans with decades-long careers who would never budge. But with the right champion, none of it mattered.

“You’ll know them when you see them,” is all Max says. “Come on. Let’s get going.”

They put their coats back on and toss out the wax paper wrapping, a few crumbs spilling in the process.

“Next stop: Program of Record, am I right?” Phil says with a chuckle.

“Ha. Right.” Max replies.

As they step into their Uber, though, Max once again wonders about the road ahead, one that feels fundamentally at-odds with the expectations Angelica and their investors have of them.

There are number of GTM models he knows they could pursue. The dream, of course, is a contract to sell their tools at scale. But the milestones on that journey are few and far between. Along the way, it would become his job to sell these thin milestones to investors. IDIQs, OTAs, he increasingly sees TechCrunch articles trumpet these as signals, but he knows that these are not revenue. The opportunity to maybe, eventually sell is not revenue.

Yes, there are other models. Great start-ups can grow into lean R&D labs, pick up SBIRs left and right, or get acquired for parts. But there are not-only high, but fast stakes to a venture dollar. What payoff do Phil and Angelica expect from him?

Their Uber arrives and they begin the long walk to their assigned entrance. But today, as Max empties his pockets and takes off his coat for security, ID in hand, he feels optimistic.

From what he’s heard, the program officer they’re about to meet, Ms. Connie Tract, might just be their champion.

Part 3: Government is Skeptical

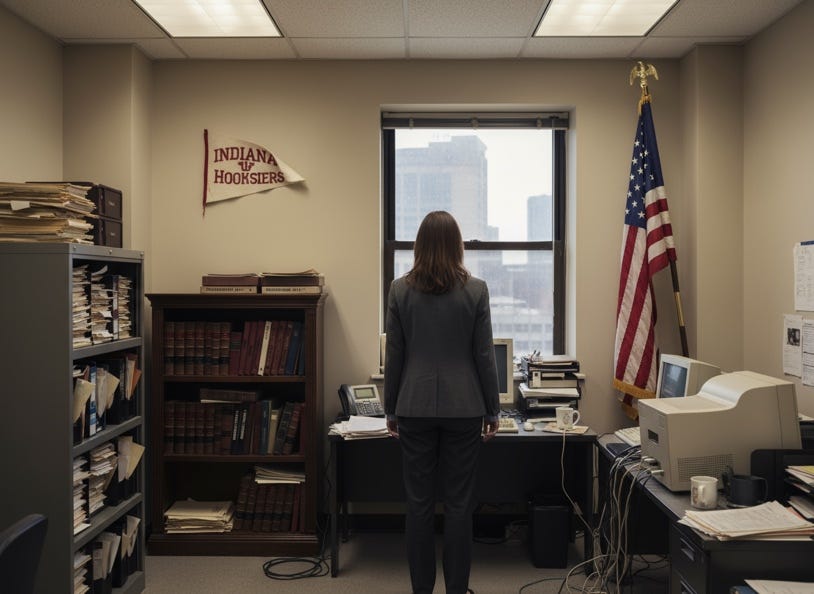

Every morning on the walk to the elevators, past swarms of suits and pencil skirts, Connie Tract passes by a water fountain. It’s the fancy kind with a sensor-enabled faucet and a running tally of plastic bottles its saved. A sign above reads: “Please do not wash dishes here.”

Connie hasn’t used the fountain in years. She only notices it when she escorts guests to her office. It’s a high security building, after all, and she has built the habit of meeting guests in the lobby to avoid the inevitable security hold-ups. Some of her guests will notice this sign and furl their eyebrows. Even fewer will ask about it.

Her meeting for that morning, CEO Phil Stack, is one of those few.

She almost never gets to meet the companies directly. To her, the Pentagon’s many vendors remain numbers on a spreadsheet. Her job is to manage a sliver of the budget that Congress sends over every year. A hundred people clamor over every $1 sent, trying to showcase their project’s urgency. It’s her job to help steer that dollar into a contract.

Someone higher up the pipeline must’ve really wanted Phil to get this dollar. That, or it was Phil’s partner, Max Clarence, who somehow knew her boss three doors down.

“What’s with the sign?” Phil asks.

Connie always responds the same way her boss did when she first asked.

“Why do you think it’s there?”

Max pauses, as though he’s worried it’s an evaluation. It isn’t, of course, but the joys in Connie’s job are few and far between.

“I don’t know. There’s a kitchen around the corner?”

“It’s because someone, at some point, tried washing their damn dishes there.”

Connie has worked at a program office in the Pentagon for a decade now. She left Indiana University with a master’s degree in public policy and a fervent, if not vague, belief in making government work better. A mentor had told her about a Presidential Management Fellowship opening at DOD, and years later, she’d stuck around.

But those first years were hellish. Dreams of the cutting-edge ran face-first into the bureaucratic wall. Years later, she was still closer to the bottom of the totem pole. But it wasn’t nothing. She’d cut her teeth over the years, pushing paper and acing every course she’d taken at Defense Acquisition University (a name she initially thought was a joke before realizing it was an actual school). Now, whenever she hears from twenty-eight-year-olds in Allbirds, she knows what to listen for.

But Phil, to his credit, was already doing better than most.

Think piece after think piece excoriate procurement, the sheer capture by the primes, the constant pressure from above and below the hierarchy on every decision. Connie should know, she’s contributed to more than her fair share of articles for Brookings and CSIS and the like. She counts every start-up contract that she’s pushed through as a career achievement. She’s not one to miss brilliance.

But that’s the problem with the Valley types. They think brilliance is enough.

What they don’t understand is that government is hard. The military is hard. She’s not one to be grandiose, but this much is true: lives are at stake. These are billions in taxpayer dollars. These technologies are expected to support operations at an incomprehensible scale.

There’s an inherent difference at play as well. A company’s concern is its bottom line. But for the military and government, it’s the mission. Disdain for the documentation, the paperwork, the meeting minutes, it all translates into disdain for something far greater.

These things exist because someone, at some point, tried to wash their dishes in the water fountain.

The trio arrives at her office, which Connie has decorated to the best of her ability. A Hoosier pendant hangs limp on the wall behind her; she keeps forgetting to grab the tape from down the hall.

They get into the business at hand, which is a mere sliver of the months-long gauntlet Phil and Max will have to endure. She feels compelled by this team, though, not only because of their tech, but because it feels like Phil respects the world he’s entering.

She wants to believe him. She certainly believes the numbers, the testimonials, and the vision.

But there’s a bigger question at hand.

Phil and his peers’ companies are perched upon this premise: that start-ups can make do on promises to revolutionize government services. That their products – cheaper and better than those of the primes and incumbents – can carry this weight on their shoulders.

The government is skeptical of that promise.

It’s not skeptical out of a desire for dismissal. No one likes the primes; everyone shares the same dreams of innovation.

But it’s skeptical by design. Feature, not bug. Interoperability matters with 2 million uniformed personnel. Materials sourcing. Data security. And if we go to war, what then? How many Programs of Record should they be handing out? What’s Phil going to do, power the US military with his Series Q?

She’s being glib. It’s hard not to be in the thick of the bureaucratic maelstrom.

Connie knows her job is to be risk averse, because the end users are taking the greatest risks of all. Arguments about the degree of skepticism, the degree of risk aversion? She knows these are fair. Lord knows how often she’s stuck her neck out to move this needle. She agrees that too many incumbents, who snuck past the finish line a century ago, have been free to overpromise and underdeliver for decades, leaving taxpayers to foot the bill.

But degree is a hard question. The continuous vs. the discrete. When people call for reform, it begs the follow-up: what level of risk are you willing to accept?

Today, though, as Phil explains his integration of the latest feedback from the General, the potential commercial applications for his dual-use batteries, and the supply chain changes they’re exploring to comply with Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR), she thinks she knows.

Maybe cautious excitement is the right answer.

“Anything else?” Phil asks.

“Let’s talk next steps,” Connie replies.

Part 4: Government is Mission

At this point in the story, there are several directions Phil’s start-up might take.

Perhaps he succeeds. With the help of Connie Tract, the company eventually receives an OTA, through which they pen their first revenue-bearing contracts. After a few more rounds of fundraising, hiring, and spending, these contracts grow until his start-up is no longer a start-up and is a respected vendor to a slate of government and commercial customers. Ten years later, they’re addressing America’s most pressing questions: edge-power, grid revitalization, EVs, and more.

Angelica follows on from her pre-seed check, building a burgeoning fund off the company’s success. Max Clarence now commands a GTM army out of DC. Connie’s eye for winners and her steady hand in navigating bureaucracy catapult her through the ranks.

But let’s not mince words. It’s a tough business, and perhaps Phil’s start-up burns in the proverbial valley of death. Even with an OTA and future fundraising, any number of crises might derail them. Maybe their ultra-cheap batteries were no longer so cheap once they couldn’t source from China. Maybe a handful of pilots was one thing, but the sheer scale that operators demanded remained out of reach. Maybe Phil enjoyed the temptations of multi-million capital raises a little too much.

In the event of failure, the most likely outcome, some might say that the government screwed up, that it lost out on a great innovation by not supporting a team ready to deliver. Others might say the government did exactly what it was supposed to do, ensuring taxpayer money was spent on reliable products.

But ultimately, people at every stage of the pipeline were exactly that: people. They navigated complex and often limited decision landscapes. They took risks – risks that may have looked inconsequential to one another but were meaningful nonetheless – and stuck by them.

The government is a lot of things as a customer. It is desperate, it is champions, and it is skeptical.

But ultimately, it’s driven by mission, not all too different from the start-ups trying to sell to it.

Acknowledgements

This series would not have been possible without the many people who took the time to chat: Delian Asparouhov, Nathan Bergin, Matej Cernosek, Corey Jacobson, Zak Kirstein, Eric Lasker, Troy LeCaire, Nate Loewentheil, Connor Love, Michael Lumley, Arul Nigam, Daniela Perlein, Navneet Vishwanathan, Ellen Waters, Pat Williams, and more.

Thanks also to Mike Annunziata and Brandes Woodall at Also Capital for giving me the best crash course in VC and early-stage tech I could ask for. They’re doing great work and it was an awesome experience to tag along for the fall.

About the Author

I’m Atharv and I’ve spent my life studying the intersection of tech and government. I researched India’s digital payments infrastructure as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, liaised with tech start-ups at the US State Department and the World Bank, and spent this past fall as a fellow at Also Capital. I’m also a writer, with a newsletter about movies, and an ongoing novel about the British East India Company in 18th century Bengal.

You can get in touch with me at atharv.gupta@gmail.com.