Just follow the talent

Its what the math says

I’ve taken the Also Blog Post pen again!

This time, I want to unpack one of venture investors’ favorite quotes to tweet and retweet: “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” Robert Solow, the Nobel Laureate economist behind the Solow growth model, wrote this line in a New York Times article in 1987. I think it’s often misrepresented and stripped of the nuance he intended, so I wanted to offer my attempt at an interpretation. TL;DR: I think it means that talent density wins, and it takes a long time for everyone else to catch up.

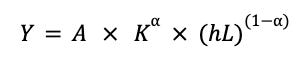

The Solow growth model helps explain whether an economy is growing because it’s adding more inputs (capital and labor) or because it’s using those inputs more efficiently. Solow found that only 1/8th of the increase in U.S. labor productivity between 1909 and 1949 could be attributed to increased inputs. America, in other words, became great through technological innovation (A) and improvement in the quality of its labor base (h). One version of the macroeconomic production function looks like this:

It’s complicated, but technology (A) and human capital (h) are effectively the only levers a company1 can pull. Together, they define your ability to differentiate, attract better (less elastic) labor (L) and capital (K), and ultimately build something enduring. A and h are what shift your function up and to the left, placing you on a different playing field than your competitors – a step change, if you will.

Put differently, A is the external technology frontier, (what’s technically possible), and h is the internal capability to reach it. Maximum value creation is achieved only when the two work together. If A rises but h stagnates, the technology exists but its benefits aren’t realized – a diffusion gap. IMHO, this is what Solow is referring to when he said that “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics” in July 1987.

The computer age was revolutionary, but not enough people were using the technology well enough for its impact to register at the macro level. In fact, Solow later clarified in multiple interviews that the computer age did show up in the macro productivity statistics very shortly after, fueling the massive boom from 1987 to 1995. He also noted that the gains were highly concentrated. A small set of companies and industries captured the vast majority of the benefits immediately, while others took years or decades. The big winners were early adopters – the ones that jumped the shark, made it across the diffusion gap, and realized the value first and most fully.

How did they do it? According to Solow, these industries and companies had better human capital (higher h) — and crucially, a lot of it (hL). To benefit from A, follow h. Look for the people who can create and use novel technologies for the best purposes, and when there is a lot of h in one place, hL, figure out how to get them some K. And so, with loose but entirely defensible ties to math, statistics, and economics, you can show that the thing that matters most — arguably the only thing that matters — is talent density. Everything else is downstream of getting the people right.

The Solow model was designed to evaluate economies, but I think it applies well to companies, especially early-stage ones, with some adjustments and forgiveness around the edges.

I like what I am reading ‼️

Always the best reads!!! Go Brandes!