Consensus Founders, Non-Consensus Ideas, and the Shape of $10B Outcomes

Engaging in a fun debate to start the new year

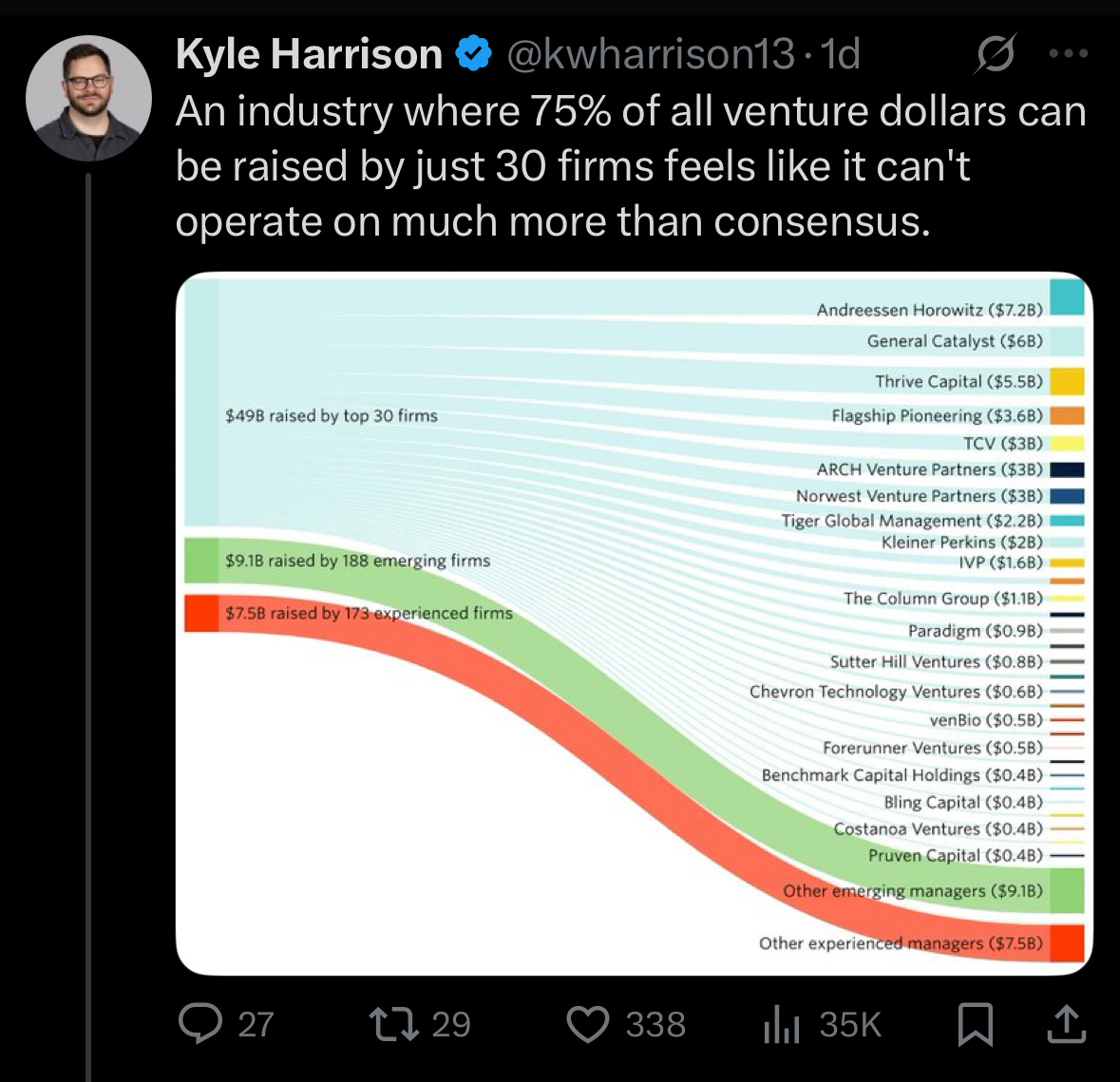

There’s a lot of chatter right now about “consensus founders” versus “non-consensus founders,” usually framed as a failure of imagination or a herd mentality among investors. Here’s an example:

But my view is that framing misses something more fundamental. When more capital is raised, the exit size goes up. What a $10B+ company requires in its earliest innings is very different than a $1B+ company. Very large outcomes are not just bigger versions of smaller ones. They are qualitatively different trajectories. Those trajectories demand a different optimization function at the start.

At the extreme end of outcomes, the early constraint is rarely idea originality alone. The constraint is whether the company can rapidly assemble a world-class team, attract disproportionate capital, and deploy that capital early enough to unlock a path that compounds at massive scale. Leadership and talent density matter more than the precise initial insight.

This is why some founders look “consensus” to investors. It’s not because the idea is obvious. It’s because the person is legible as someone who can recruit aggressively, make senior hires ahead of proof, raise large rounds before revenue, and carry organizational complexity far earlier than most startups ever need to.

If your goal is to build a $10B company, the first few years are not primarily about being right. They are about building an engine that can move fast once you are directionally right. That engine is people plus capital.

Earned insight still matters, but it matters differently. At smaller outcome scales, insight is the wedge. It is a sharp, asymmetric understanding that lets a small team outmaneuver incumbents with limited resources. At very large outcome scales, insight is often table stakes. The real differentiator is whether the company can turn partial insight into momentum faster than competitors by hiring better, spending earlier, and scaling decision-making without collapsing.

This explains a pattern that can look uncomfortable from the outside. Investors sometimes back founders with familiar pedigrees, repeat success, or obvious leadership gravity. Not because novelty is unimportant, but because these founders are more likely to survive the capital-intensive, coordination-heavy phase required to reach escape velocity.

In other words, early idea quality and early leadership quality do not scale linearly with outcome size. The bigger the potential outcome, the earlier leadership, recruiting, and capital formation dominate.

Non-consensus founders still win. Many of the most important companies in history started that way. But they often win by becoming consensus over time, by proving their ability to attract talent, command resources, and lead organizations well before the market fully understands the idea.

Seen this way, the consensus versus non-consensus debate is a proxy for a deeper question. What are you actually underwriting at the seed stage?

If you’re underwriting a $1 to $3B outcome, sharp insight and scrappy execution can carry you a long way. If you’re underwriting a $10B+ outcome, you’re underwriting the founder’s ability to build a high-talent institution under extreme uncertainty.

Different outcome targets require different things early. Confusion arises when we pretend they don’t.